Table of Contents

Why "Press Brake" Called Press Brake?

The nomenclature of a press brake raises curiosity—why is it termed as such, rather than a straightforward "sheet metal bender" or "metal former"? Is there a connection to the old flywheel on mechanical brakes, where the presence of a brake, akin to a car's, enabled control over the ram's motion during sheet or plate forming? The notion that a press brake is essentially a press with a brake has lingered in my understanding, shaped by years of hands-on experience. However, specilists question the accuracy of this assumption, especially considering the historical use of the term "brake" in the context of sheet metal bending predates the era of powered machines. Moreover, the term "press break" seems inaccurate, as nothing is intended to be broken or shattered in the process. Let's unravel this terminology mystery with a nuanced exploration.

Origin of the Name of "Press Brake"

In experts quest to demystify the origins of the term "press brake," I delved into the history and etymology of sheet metal shaping. Long before the advent of powered machines, the manual shaping of sheet metal was a meticulous craft, employing tools such as T-stakes, ball peen hammers, and forming bags filled with sand or lead shot. The evolution from these artisanal methods led to the invention of the cornice brake in 1882, marking an early departure into more mechanical approaches to bending sheet metal.

The transition from manual techniques to powered press brakes began around a century ago, introducing flywheel-driven machines in the 1920s. Subsequent decades witnessed the evolution of hydromechanical and hydraulic press brakes, followed by electric press brakes in the 2000s. Despite these advancements, the question persists: why is it called a press brake?

The answer lies in the etymology of the term "brake." Words like "broke," "brake," "broken," and "breaking" trace back to archaic terms predating the year 900. Old English, Dutch, German, and Gothic variations led to the evolution of the term "brake," initially defined in the 15th century as an "instrument for crushing or pounding." Over time, it became synonymous with "machine," derived from its use in crushing grain and plant fibers.

The Old English term "brecan," evolving into "break," highlighted the violent division of solid objects. The past participle, "broken," emphasized the close connection between "break" and "brake." In Middle English, "brake" meant to bend, change direction, or deflect, extending its meaning beyond physical destruction.

The term "press," unrelated to journalism or publishing in this context, finds its roots around 1300 when it meant "to crush or to crowd." By the late 14th century, "press" had evolved into a device for pressing clothes or squeezing juice from grapes and olives. This transformation continued, ultimately referring to a machine or mechanism applying force through squeezing.

In essence, a press brake merges the Middle English verb "brake," signifying bending, with the concept of a machine applying force through pressing. Despite the accuracy of the term, the journey from manual craftsmanship to powered machines has introduced various iterations, including leaf brakes, mechanical, hydromechanical, hydraulic, and electric press brakes. As technology advances, modifiers reflect the machine's actuation, tool usage, or bending types. Regardless of the terminology, a press brake remains a versatile machine for crushing, squeezing, and, in our context, bending sheet metal.

From T-stakes to Cornice Brakes

Before machines came along, if someone wanted to bend sheet metal they’d attach an appropriately sized piece of sheet metal to a mold or a 3D scale model of the desired sheet metal shape; anvil; dolly; or even a forming bag, which was filled with sand or lead shot.

Using a T-stake, ball peen hammer, a lead strap called a slapper, and tools called spoons, skilled tradespeople pounded the sheet metal into the desired shape, like into the shape of a breastplate for a suit of armor. It was a very manual operation, and it’s still performed today in many autobody repair and art fabrication shops.

The first “brake” as we know it was the cornice brake patented in 1882. It relied on a manually operated leaf that forced a clamped piece of sheet metal to be bent in a straight line. Over time these have evolved into the machines we know today as leaf brakes, box and pan brakes, and folding machines.

While these newer versions are fast, efficient, and beautiful in their own right, they don’t match the beauty of the original machine. Why do I say this? It is because modern machines are not produced using hand-worked cast-iron components attached to finely worked and finished pieces of oak.

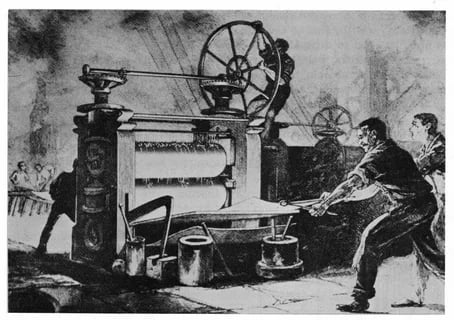

The first powered press brakes appeared just about 100 years ago, in the early 1920s, with flywheel-driven machines. These were followed by various versions of hydromechanical and hydraulic press brakes in the 1970s and electric press brakes in the 2000s.

Still, whether it’s a mechanical press brake or a state-of-the-art electric brake, how did these machines come to be called a press brake? To answer that question, we’ll need to delve into some etymology.

Brake, Broke, Broken, Breaking

As verbs, broke, brake, broke, and breaking all come from archaic terms predating the year 900, and they all share the same origin or root. In Old English it was brecan; in Middle English it was breken; in Dutch it was broken; in German it was brechen; and in Gothic terms it was brikan. In French, brac or bras meant a lever, a handle, or arm, and this influenced how the term “brake” evolved into its current form.

The 15th century definition of brake was “an instrument for crushing or pounding.” Ultimately the term “brake” became synonymous with “machine,” derived over time from machines used to crush grain and plant fibers. So in its simplest form, a “pressing machine” and a “press brake” are one in the same.

A press brake doesn’t “step on the brakes” to bend, so why is it called a press brake? A brief history of a few words reveals the answer. Photo courtesy of Getty Images.The Old English brecan evolved to become break, meaning to violently divide solid objects into parts or fragments, or to destroy. Moreover, several centuries ago the past participle of “brake” was “broken.” All this is to say that when you look at the etymology, “break” and “brake” are closely related.

The term “brake,” as used in modern sheet metal fabrication, comes from the Middle English verb breken, or break, which meant to bend, change direction, or deflect. You could also “break” when you drew back the string of a bow to shoot an arrow. You could even break a beam of light by deflecting it with a mirror.

Who Put the ‘Presse’ in Press Brake?

We now know where the term “brake” comes from, so what about the press? Of course, there are other definitions unrelated to our current topic, such as journalism or publishing. This aside, where does the word “press”—describing the machines we know today—come from?

Around 1300, “presse” was used as a noun that meant “to crush or to crowd.” By the late 14th century, “press” had become a device for pressing clothes or for squeezing juice from grapes and olives.

From this, “press” evolved to mean a machine or mechanism that applies force by squeezing. In a fabricator’s application, the punches and dies can be referred to as the “presses” that exert force on the sheet metal and cause it to bend.

To Bend, to Brake

So there it is. The verb “brake,” as used in sheet metal shops, comes from a Middle English verb that meant “to bend.” In modern use, a brake is a machine that bends. Marry that with a modifier that describes what actuates the machine, what tools are used to form the workpiece, or what types of bends the machine produces, and you get our modern names for a variety of sheet metal and plate bending machines.

A cornice brake (named for the cornices it can produce) and its modern leaf brake cousin use an upward-swinging leaf, or apron, to actuate the bend. A box and pan brake, also called a finger brake, performs the types of bends needed to form boxes and pans by forming sheet metal around segmented fingers attached to the upper jaw of the machine. And finally, in the press brake, the press (with its punches and dies) actuates the braking (bending).

As bending technology has progressed, we’ve added modifiers. We’ve gone from manual press brakes to mechanical press brakes, hydromechanical press brakes, hydraulic press brakes, and electric press brakes. Still, no matter what you call it, a press brake is merely a machine for crushing, squeezing, or—for our purposes—bending.